I was recently prompted to write about the essence of APIs and the role they play in the construction of software systems, as well as the potential downstream benefits they afford. I also discovered that a reasonable amount of confusion surrounds the term, which tends to surface during discussions about integrating systems. Like most things in life, the more we understand about any given concept, the easier it becomes to construct simple and intuitive mental models.

First things first… what does the acronym API mean?

API is shorthand for Application Programming Interface. The second word (programming) gives us an important clue–this is an interface that is visible to software engineers during the process of programming. The word interface also gives us another clue–you can think of this as a connection point where two things come together.

The notion of an API is indeed not a new concept in software design. The idea in relation to software dates back to the beginnings of computing and especially during the introduction of high-level programming languages. It is a basic building block in the design of software systems. The ubiquity of Internet protocols, coupled with the principles of the web (small pieces loosely joined), created the perfect storm for truly leveraging the purported benefits of APIs. It is not uncommon these days to hear software companies talk about being API-first or API-centric.

If you remember only one thing, remember this… an API is essentially a contract between a consumer and a provider.

This is illustrated quite nicely using an analogy from everyday life. The socket below is essentially an interface, not just in form–which is obvious–but also in function. The specification of the interface also states that 220V of power will be generated in alternating current (AC). This is indeed critical information, because a manufacturer of products that require power, such as toasters, will design those products in accordance with the specification. Not only must the plug be designed according to form, but the internal mechanisms must be able to work with 220V AC power. In this example, the consumer is the toaster and the provider is the socket.

In the world of software, the terms consumer and provider are used in a general sense, but in essence, they are just programs. A consumer is typically an application and a provider is usually a service. However, it is perfectly reasonable for one service to act as a consumer invoking an API provided by another service.

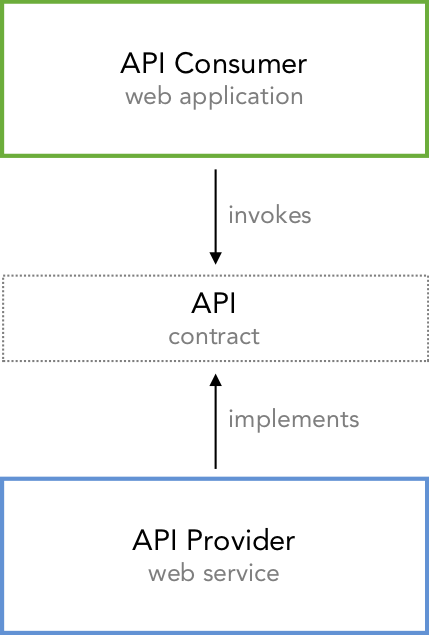

The following is a simple diagram depicting the relationship between an API (contract) and its consumer and provider.

APIs are important building blocks in the construction of software systems. They promote modularity and the separation of concerns, which says that some function, whatever it may be, can be isolated from other parts of the system in such a way that it can be substituted in the future. A contract (API) is a beautiful thing for sure, because it allows both the consumer and the provider to evolve independently. You might quizzically raise an eyebrow, questioning why evolvability is all the rage, but it is this architectural property that plays a large role in determining the cost and complexity of change.

Consider the above-mentioned toaster example. While a socket is unlikely to change much, the toaster manufacturer may create new and innovative products every year, all conforming to the same socket interface. As you can see, the contract plays an important role in the independent evolution of things that connect with each other. Software systems are essentially the same–lots of components that interconnect with each other using programming interfaces.

The reason that API has surfaced in the executive ranks as a household term, and not forever banished to the cubicles of software engineers, is the potential for monetization outside traditional application channels as well as the ability to create stickiness inside the enterprise. By encapsulating key business functions into services and exposing them via APIs, companies now have a channel for extending their reach into the enterprise by enabling deeper integrations across the IT landscape. This so-called stickiness heightens the replacement cost of those systems. Further, it opens up another potential channel for generating revenue.

I could wax-poetic about interfaces and contracts, and so on, but I suggest we come in for a landing before things get completely wonky. Despite briefly exploring the concept of APIs, their design is an entirely different endeavor that often requires a blend of artistic and scientific thinking, a topic deserving of its own post.