One admitted benefit of spending nearly three decades in the field of software engineering is the accumulation of wisdom that comes from connecting various dots throughout the evolution of software systems. Those connections stem from a candid retrospective of design decisions, many of them early and seemingly benign, that when linked together had a profound impact on the evolutionary path of those software systems.

The dots, in this case, refer to matters of software architecture, arguably the most influential component of longevity and adaptability in the context of continuous change. The wisdom, likewise, refers to a practical understanding of the relation between software architecture decisions and the cost and complexity of future modifications.

Consider this scenario…

Suppose you have been commissioned to design a building that will start with a single floor, but the expectation is that additional floors will be erected as demand warrants. As one can imagine, the architectural considerations will be markedly different than those pertinent to, say, a structure with twenty floors. A twenty-floor building would likely require that foundational pillars penetrate the earth much deeper, installation of elevators to efficiently transport people between floors, and the presence of safety systems for quick evacuation in the event of an emergency.

In the interest of realizing early returns on investment, do you forego the architectural requirements of a twenty-floor building and focus instead on a single-floor design?

In the field of structural engineering, such a choice would be financially disastrous because the implication of retrofitting new architectural requirements would probably entail demolition of the existing building.

In the field of software engineering, though, this sort of behavior happens every day because the cost of demolishing source code is essentially free. If a prior decision proved to be wrong, perhaps due to changing requirements, intentional avoidance or blissful ignorance, large swaths of source code can be deleted with a few keystrokes.

Of course, the idea that software modification comes without cost is pure fiction, though surprisingly, there is often a lingering subconscious belief otherwise, stemming in large part from increasingly sophisticated capabilities in modern development toolchains.

One of the things we consistently do as software engineers is make tradeoffs during the development process. Those tradeoffs represent a balance between business objectives–getting products and features to market as quickly as possible–and technical objectives–designing software architectures that easily adapt to change. Such is the eternal struggle between doing the right things and doing things right.

How does all of this relate to monoliths?

The postulation is that the majority of software systems begin life as simple monolithic architectures, primarily attributed to business pressures favoring speed-to-market over architectural correctness, and expand over time into complex monoliths whose permanance can only be reversed through divine intervention or deep pockets.

An explanation for the making of such monoliths is in order…

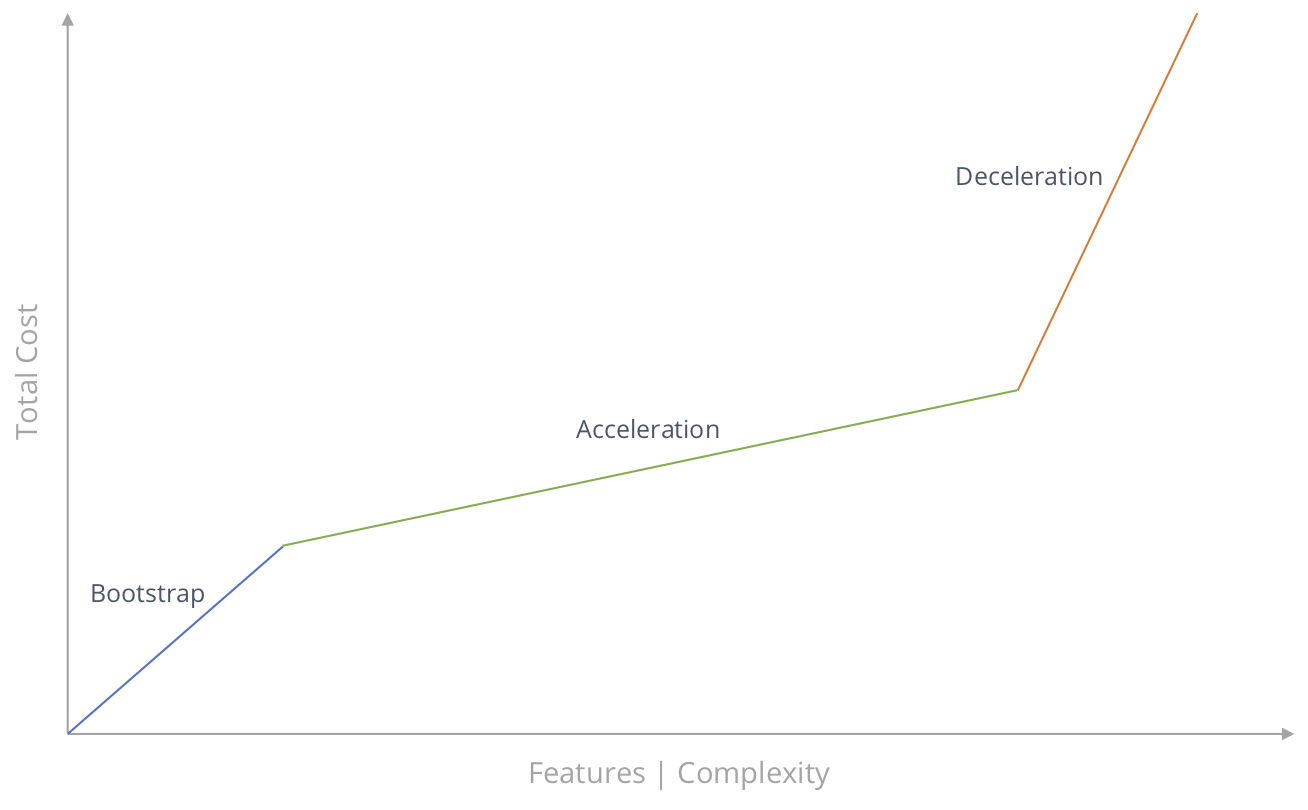

Below is a simple graph depicting the crude relationship between feature accrual and the total cost of development. Monolithic architectures are often cemented during the glory days of acceleration.

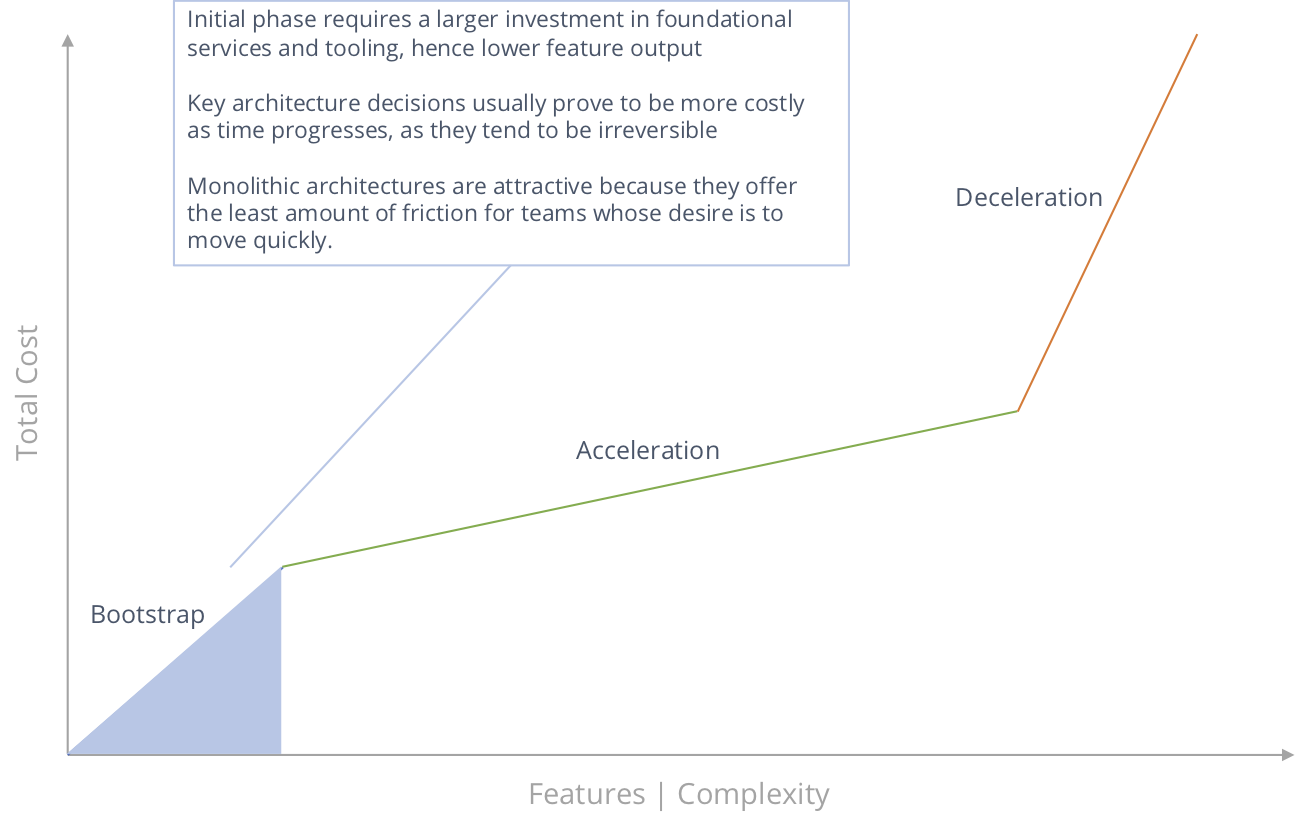

During the bootstrap phase, there is usually some degree of fixed cost to develop foundational capabilities reflecting key design decisions. In essence, these decisions represent the nascent architecture. During this phase, the primary motivation is to move fast and remove obstacles, often at the expense of making short-term architectural decisions.

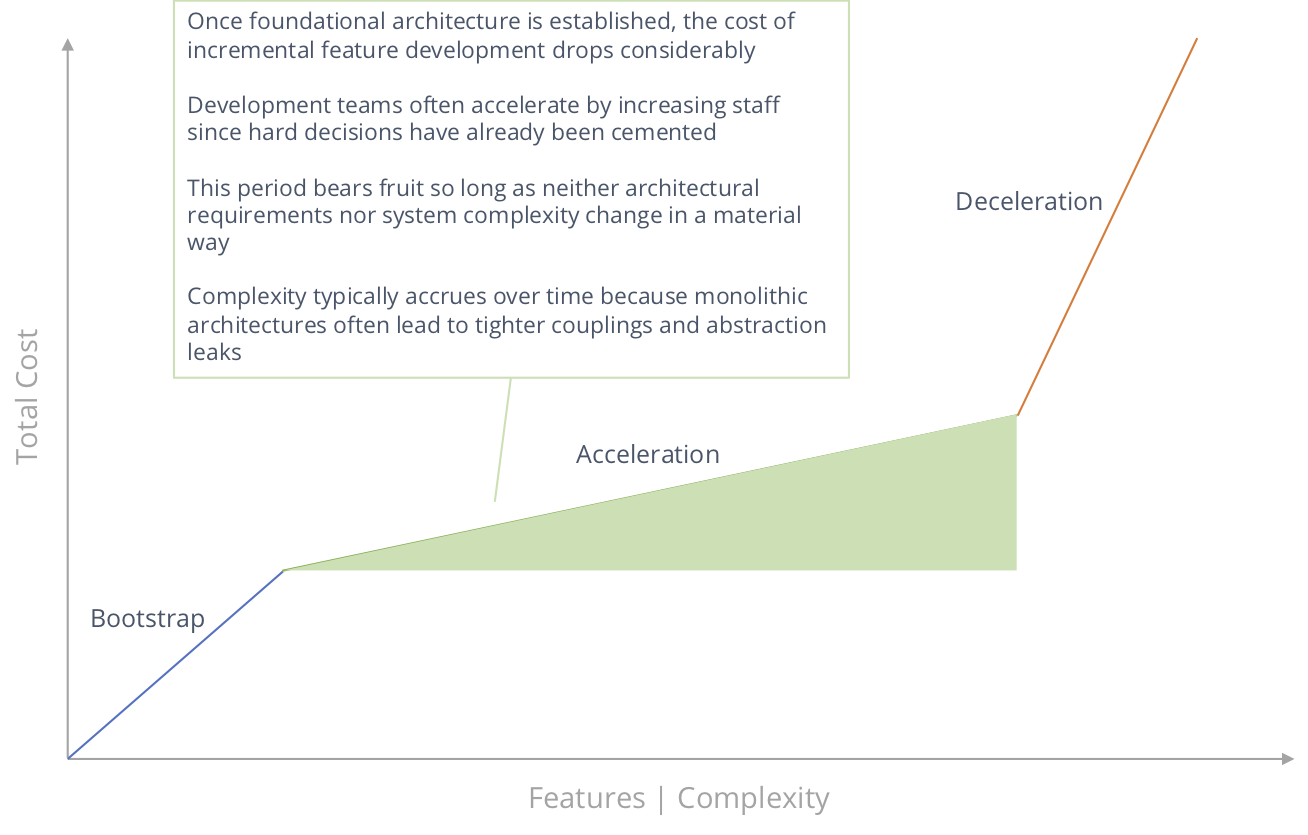

The acceleration phase occurs when enough architecture exists to enable expansion of the development team for the purpose of scaling feature delivery. These are glory days indeed, as the incremental cost of new features is comparably lower given that all of the key structural decisions have been etched in stone.

A period of acceleration can thrive for years so long as changing requirements do not challenge the structural forces of the monolithic architecture. What often happens during this phase, largely attributed to the nature of monolithic systems, is that couplings between components tend to become tighter due to abstraction leaks and other forms of modularity violations. The complexity trap is being set!

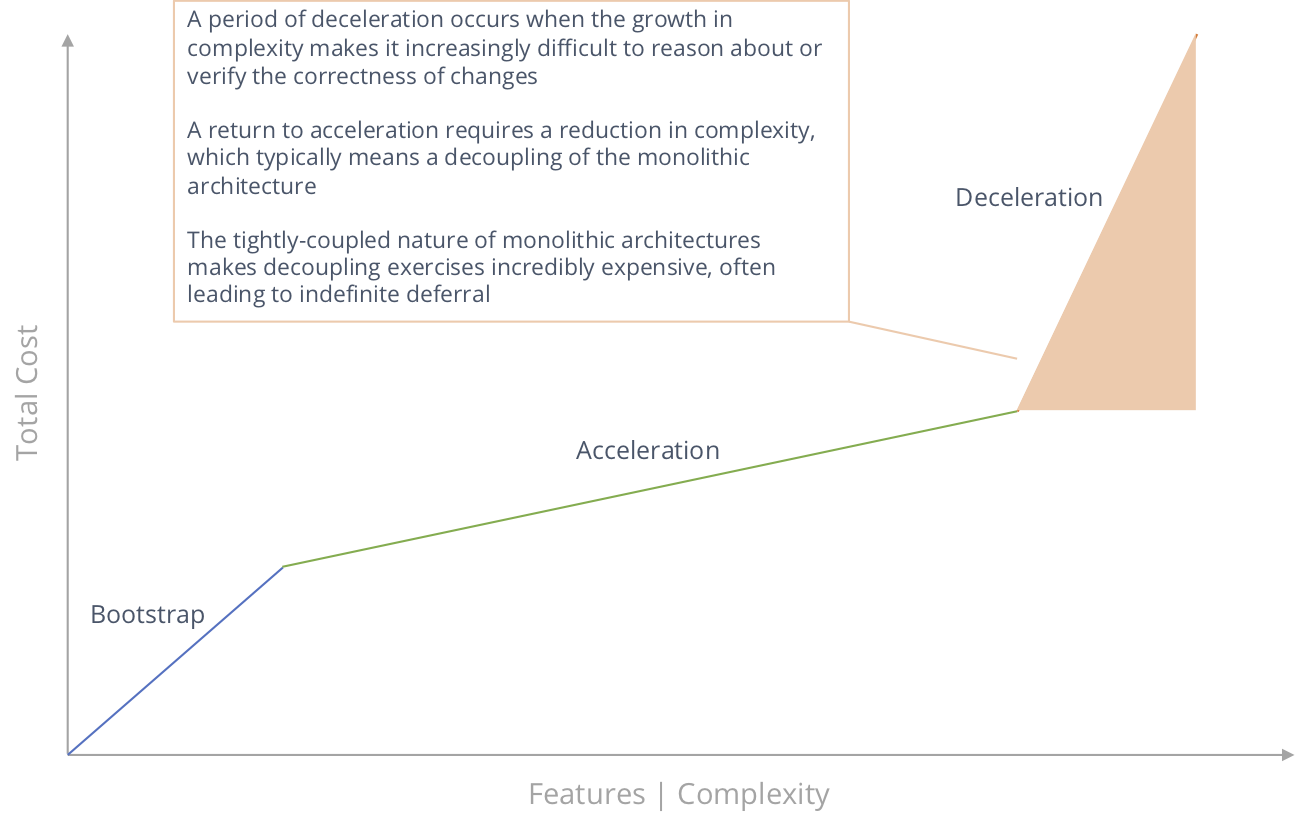

The deceleration phase activates when complexity accrues to a point where the cost of change begins to increase substantially. The problem is that complexity usually accumulates slowly, similar to the manner in which years of a sedentary lifestyle leads to heart disease.

The only practical means of returning to a period of acceleration is to reduce the complexity, and that requires architectural decoupling. At this point, most businesses are unwilling to invest the time and money to exercise such efforts. There is indeed wisdom in questioning the merits of such investments and their expected returns. In many cases, there is simply no business case to revisit the architecture of an existing system.

Oddly enough, most software systems predictably follow this architectural path despite the fact that few businesses actually desire such an outcome.

This post is not an indictment or criticism of monolithic architectures, only a means of raising awareness to development teams and business leaders that accrual of complexity ultimately leads to slower and more expensive change.

The reality is that software architectures need constant care and feeding in the same way we think about products that might be suffering from aging user interfaces and absent features.